Invasive Insect Spotted in North Carolina

go.ncsu.edu/readext?881243

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲NC State Extension and North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services experts have kept a wary eye to the north since first hearing tales of the spotted lanternfly a few years ago.

The invasive insect, native to parts of Asia, was detected in Berks County, Pennsylvania, in 2014. It began moving south, into Maryland, West Virginia and Virginia. It seemed inevitable that it eventually would arrive in North Carolina.

“Last year we knew that the spotted lanternfly was already in several Virginia counties that were bordering North Carolina, so we knew it was only a matter of time” said Phyllis Smith, an agent specializing in natural resources and environmental systems with N.C. Cooperative Extension’s Forsyth County center. “Insects cross borders.”

Sure enough, the first documented established population of spotted lanternfly was found in Forsyth County in June.

The top view of an adult spotted lanternfly.

That is concerning news for some segments of the state’s agriculture industry. The lanternfly is a destructive insect, with a diet that includes grapevines and fruit trees. The initial infestation is a worry for grape growers particularly, since Forsyth County is the gateway to the Yadkin Valley, where much of the state’s wine industry is located.

“The western border of our county borders the Yadkin River,” Smith said. “We are a part of the Yadkin Valley where the grape production is very, very important to our agricultural economy. Grape producers need to be very vigilant right now and be looking on their vines for the insects or signs of them.”

Related: NC State Extension tips for spotting the spotted lanternfly, and what steps to take

Based on what the spotted lanternfly has done in other states, the threat is very real.

“The biggest worry right now is viticulture, winemaking grapes,” said Kelly Oten, NC State Extension specialist in forest health. “If they attack in high numbers, they can kill grapevines pretty quickly. If they don’t kill it, they greatly reduce the grape crop. They see up to 90% reduction in crops. And the grapes that do remain have an altered sugar content. It just messes the whole system up. There’s going to have to be a lot of management that is put into place with a lot of grape growers in North Carolina.”

Grapes and the wine industry are not the only agricultural commodities at risk.

“This is probably not going to be a tree killer, but it will affect many different hardwoods like maple and walnut and will attack fruit trees as well,” Oten said. “They attack apple and stone fruit trees, and potentially hops, things like that. The thing is, they’re not picky. They have been documented on over 100 plant species.”

The public has a key role to play in managing the spotted lanternfly. Perhaps the key role. Efforts to mitigate the pest won’t be possible without North Carolinians seeing them and reporting them.

“It’s very important that we’re all very vigilant about this and we’re looking out for it,” Smith said. “People have sent me photos of things that were not spotted lanternflies. That’s great. People are looking for it, and that’s a good thing.”

When people see — or think they see — a spotted lanternfly, they are asked to take a photo and submit it through the North Carolina Department of Agriculture’s online reporting tool. The NCDA will evaluate the photo, determine if it is a lanternfly and if it is part of an infestation, and take appropriate steps.

Of course, to report it you have to be able to recognize it.

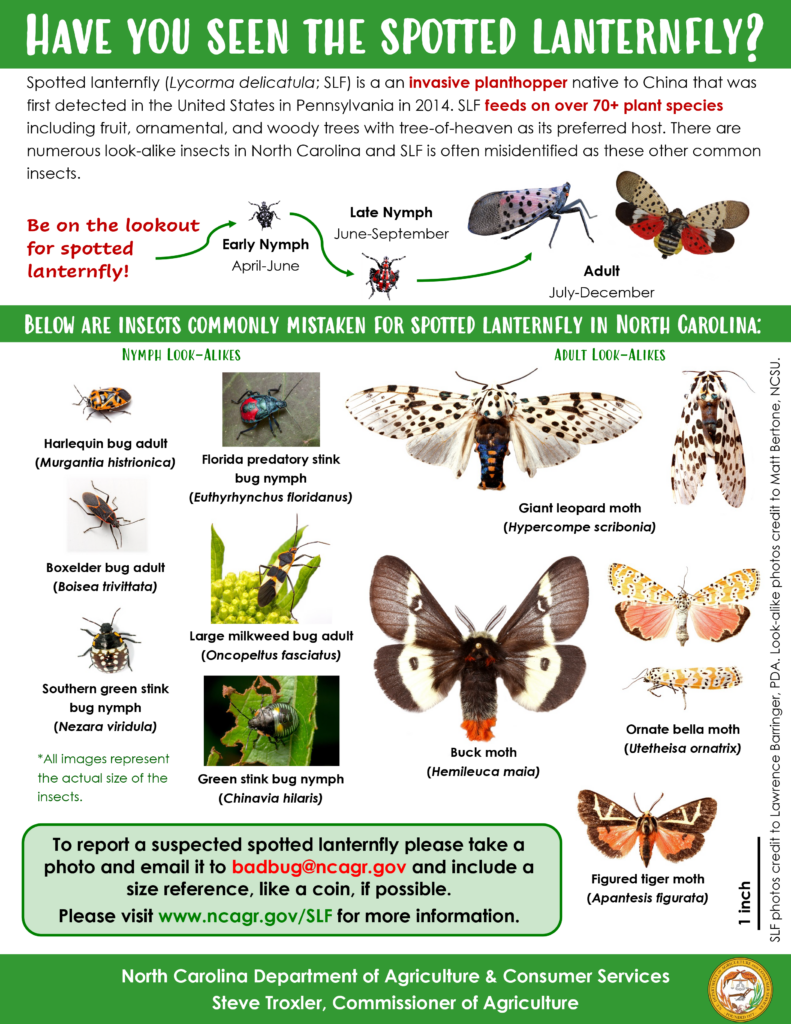

“The biggest thing you can do to help is to become familiar with what it looks like,” Oten said. “When it’s an egg mass it looks like a smear of mud. When it’s a nymph it goes through two different color morphs: black with spots, and black and red with white spots. Then, as an adult it has black-spotted gray wings with red underwings. Becoming familiar with how it looks and what stage it’s expected to be in at any different period in the year will be a huge help. And of course, if you think you see it, report it!”

Also important in the identification process is knowing how large it is.

“I’m getting questions about how big is it?” Smith said. “That’s a great question because a lot of those pictures of the adults are so close-up you get the impression that this is a huge insect, and it’s not. From the head to the tail of an adult is about an inch. We can slow down the spread by getting out information like that. If people are able to quickly recognize it, that helps us manage it better.”

Extension agents around the state have been briefed on the different stages of the spotted lanternfly so they can educate the public.

“Extension is primarily working on the educational aspect, the outreach aspect,” Oten said. “We’ve been hosting internal workshops so our Extension agents are aware of what’s going on and how to respond to the general public. We did the same for the North Carolina Forest Service. We have a couple of new infographics, showing some lookalikes. If anyone thinks they’ve seen a spotted lanternfly they can compare it to that.”

While the NCDA is the primary agency in mitigating the effects of the spotted lanternfly, vital information will always be available through Extension.

“The role of Extension is to stay on top of things,” Smith said. “We will always have the most up-to-date information available. I tell people, put ‘spotted lanternfly ncsu.edu’ into a search engine. You’re not only going to get dependable science-based information, you’re going to get the most recent information.”

There are unknowns about how the spotted lanternfly will adapt to warmer climes as it moves south. Extension will conduct research into that and other aspects of the insect’s behavior.

“If you look at all the graphs showing the lifecycle of the spotted lanternfly, you’re going to see that adults don’t show up until July or August,” Oten said. “In North Carolina we had adults in June, so the life cycle is definitely different here. It is accelerated because it gets warmer sooner and insect developmental rate is based on temperature. We’re also wondering what new hosts it will start attacking now that it’s coming into a range where there’s more species of plants it can feed on. What are the new threats in the southern states?”

While the public is being asked to report sightings of spotted lanternflies, the NCDA will take over if there is an infestation.

“This isn’t something that homeowners are going to have to treat themselves for now,” Oten said. “The department of ag will be out there quickly, doing the treatments at no cost to the homeowner.”

For individual spotted lanternflies, the public can help in another way.

“If you see it or think that you see it, take a picture, report it and kill it,” Oten said.

That’s especially important in the summer. Although researchers may pinpoint differences in the spotted lanternfly’s life cycle in North Carolina, current scientific knowledge indicates this is the best time to keep them from reproducing.

“The females don’t start laying eggs until mid September,” Smith said. “So any female you can squish from now until the middle of September likely hasn’t reproduced yet. That’s important. We want to squish them anytime we see them, but if you see one after mid September she may have already laid 100 eggs. Now is a very important time to look for them and be taking those kinds of actions.”

Trees and grapevines are the primary hosts for the spotted lanternfly, but another place to look is swimming pool filters.

“One of our outreach programs is called poolside pests,” Oten said. “This insect is attracted to water. So is the Asian longhorn beetle, which is in our neighboring state of South Carolina. Essentially, pool skimmers, filters, or even pet water bowls can serve as a trap to both of these invasives. We partnered with a lot of pool companies to do outreach to their customers, asking them to report it if they see it.”

The problem with the pesky pest goes beyond agriculture. In states where the spotted lanternfly has been established, the insect has become as irritating as other notorious bugs like cicadas.

“This is going to be a nuisance pest too,” Oten said. “They’ll mass attack trees in your yard, so there’s huge swarms of these insects all over your tree and areas you like to hang out. There’s been cases where they infest downtown areas and there’s swarms of them on sidewalks, blocking entrances to restaurants and things like that.”

If that isn’t bad enough, the swarms of lanternflies likely won’t be the only uninvited guests.

“When they are feeding on a tree they secrete something called honeydew,” Oten said. “It’s a sweet sticky substance, and there’s a ton of it. A black fungus called sooty mold can grow on it and it can attract stinging insects as well.”

Related: Unlike the spotted lanternfly, there’s little to fear from the Joro spider

Perhaps fittingly, an invasive tree is the invasive insect’s preferred habitat.

“They do greatly prefer the tree-of-heaven,” Oten said. “We’ve been telling people if you want to scout for it, scout tree-of-heaven.”

Tree-of-heaven was brought from China to the U.S. more than 200 years ago. Its rapid-growing and disease-resistant traits made it a popular choice in landscaping, but it spreads aggressively and crowds out native plants.

The aggressive spread means it can be found in most areas of North Carolina, giving the spotted lanternfly no shortage of potential homes. Still, it would be challenging but fairly straightforward to contain the bugs if it only meant checking for them on the tree of heaven. That was thought to be the case when they first were found stateside, but research has shown them to be equal-opportunity pests.

“For a while we thought they needed tree-of-heaven to complete their life cycle, but that’s been debunked,” Oten said. “The fact that they attack over 100 different species of plants means that they’re going to have plenty to feed on from mountains to coast.”

So far the infestation in Forsyth County is the only confirmed one in North Carolina, although there have been other sightings.

“It’s been found 10 times in North Carolina, but each time was a one-off,” Oten said. “Extensive surveys in the surrounding area didn’t find that it had been established, it wasn’t out there in the wild.”

If the insect spreads and begins to attack agriculture it could pose additional hardships on producers beyond crop damage and loss. Some states have imposed quarantines in areas teeming with spotted lanternfly.

“If it comes to that, that’s going to be a headache for a lot of business owners,” Oten said. “Businesses operating in that quarantine zone have to take a class, and get a permit. Commodities and products may become regulated, so then you have people who have been growing things and suddenly they can’t export them. There’s a lot of cascading effects because no one else wants this insect either.”

While there is the potential if not the likelihood of negative outcomes from the advent of the spotted lanternfly in North Carolina, it isn’t cause for panic.

“I don’t want people to feel like this is just another gloom-and-doom scenario we’re going through, like we’ve been through a pandemic and now we’ve got spotted lanternfly,” Smith said. “We know so much more about it than we first did, and we’re learning new things all the time. Every time we learn something new, that helps us to come up with more efficient management tools. We probably won’t ever eradicate it. But we will find the tools we need to make it manageable so we can keep producing our grapes and our apples and our peaches and our cherries in spite of having it here. That’s the good news. That’s the silver lining.”